Doing What John Roberts Insisted Was Impossible

Perhaps the strongest passage in Elena Kagan’s unanswerable dissent in Rucho v. Common Cause was this:

But in throwing up its hands, the majority misses something under its nose: What it says can’t be done has been done. Over the past several years, federal courts across the country—including, but not exclusively, in the decisions below—have largely converged on a standard for adjudicating partisan gerrymandering claims (striking down both Democratic and Republican districting plans in the process). And that standard does what the majority says is impossible.

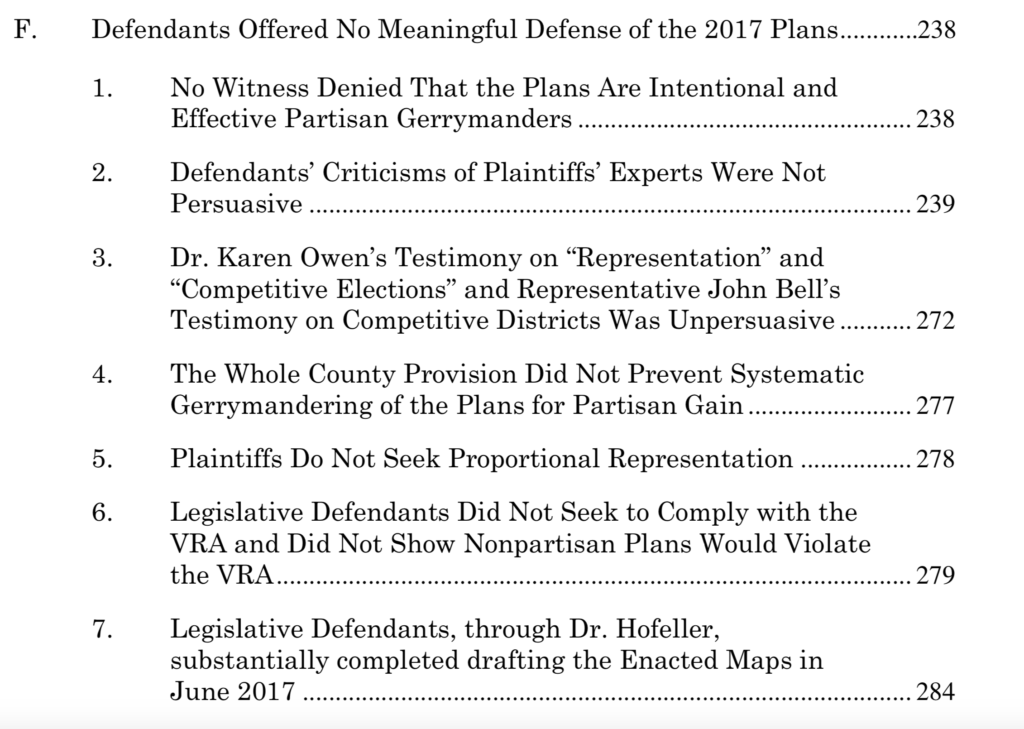

The North Carolina case from earlier this week Erik posted about is the latest example. The opinion is worth reading because of how thorough and detailed it is in dismantling the state’s case. The section headings are poetry:

Arguments that gerrymanders like North Carolina’s are consistent with the equal protection of the law are not serious, and the argument that a party entrenching itself in government irrespective of the will of the voters is even more specious. I could write a book, but if opening the channels of democracy to fair competition isn’t an appropriate subject for judicial review it’s not clear what is.

Mark Joseph Stern has more about how the North Carolina court was able to use Kagan’s dissent as a model:

The brilliance of Kagan’s dissent lay in its clarity: She laid out the precise harms inflicted by partisan gerrymandering and explained how they can be measured and remedied. Kagan identified two distinct but intertwined constitutional violations: Warped maps “reduce the weight of certain citizens’ votes,” depriving them of the ability to participate equally in elections; they also punish voters for their political expression and association. These dual injuries, Kagan concluded, implicate fundamental principles of both equal protection and freedom of speech.

After castigating her conservative colleagues for minimizing these harms, Kagan illustrated the ease with which courts can address them. In his Rucho opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts insisted that federal courts were unable to determine when a partisan gerrymander goes “too far.” Kagan pointed out that, in fact, plenty of lower courts have already done exactly that. These courts deployed a three-part test. First, they ask whether mapmakers intended to entrench their party’s power by diluting votes for their opponents. Second, they ask whether the scheme succeeded. Third, they ask if mapmakers have any legitimate, nonpartisan explanation for their machinations. If they do not, the gerrymander must be tossed out.

“If you are a lawyer,” Kagan wrote, “you know that this test looks utterly ordinary. It is the sort of thing courts work with every day.” In practice, the most important part of the test—its evaluation of a gerrymander’s severity—often boils down to a cold, hard look at the data. Take, for instance, North Carolina’s congressional map, which contained 10 Republican seats and 3 Democratic ones. Experts ran 24,518 simulations of the map that used traditional, nonpartisan redistricting criteria. More than 99 percent of them produced at least one more Democratic seat. The exercise verified that North Carolina’s map isn’t just an outlier but “an out-out-out-outlier.”

Roberts rejected Kagan’s reasoning, asserting that her test was “indeterminate and arbitrary.” But on Tuesday, the Wake County Superior Court rested its decision on precisely the three-part test that Kagan proposed. And the court deployed Kagan’s methods to demonstrate that North Carolina’s legislative gerrymander is, indeed, an “out-out-out-outlier.” Experts ran thousands of simulations to gauge the severity of the map’s partisanship and found that the current gerrymander is more favorable to Republicans than about 99.99 percent of maps drawn using nonpartisan redistricting factors.

The argument that gerrymandering represents an impossible challenge for the courts is demonstrably ridiculous on its face, and was even more ridiculous coming from the justice who gutted the Voting Rights Act without identifying any standard of review for courts to use in future cases at all. Roberts threw up his hands not because of judicial modesty but because he’s a Republican partisan and likes extreme partisan gerrymanders because they’re much more likely to help Republicans.