What Game of Thrones Got Wrong About Firebombing

Much ink has been spilled since last Sunday about the massacre at King’s Landing. Why did Dany carpet-bomb a civilian population after a city had surrendered? Was this a sign of her growing madness? Or a rational strategy to cement the legitimacy of her claim? Why didn’t the showrunners build it up better? Did they compromise Dany’s story arc as a civilian-protection advocate or were her actions always foreshadowed by her worst “fire and blood” tantrums?

In the handwringing over what Daenerys did, scant analysis has focused on how she did it. This is important since audiences draw inferences from popular culture about causal effects in real world foreign policy scenarios – such as a looming conflict with Iran. Since dragons represent air power, we should understand the historical analogy for the firebombing of King’s Landing not as the sack of medieval cities in a feudal era, but rather the saturation bombings of World War II, where undefended cities were systematically incinerated from the air.

Viewed this way, “The Bells” badly missed the mark in accurately portraying the humanitarian, operational and strategic costs of such campaigns, which the US has used before and Republican politicians have threatened to use again. In so doing, the showrunners missed an opportunity to educate its audience on the true horror of firebombing, and the way in which political actors use it at their own peril.

Fire Is Not a Precision Weapon. When Drogon begins his assault on King’s Landing, he begins with military targets – the Greyjoy naval fleet. Conceivably, fire on the ocean could be contained from spread to the civilian population on land. But once the burning of the city perimeter from the interior begins, it already beggars belief that the city’s inhabitants could be protected from the fire’s spread. This is because fire is notoriously uncontrollable – one in a category of weapons banned under international law in the real world, when civilian populations are nearby, due to its ability to spread once deployed. In short, contrary to its portrayal in the episode, Dany’s use of dragonfire already threatened the civilian population even before she targeted them directly.

When Drogon began targeting the city inhabitants directly, the showrunners portrayed the fires burning where they were ignited: in city streets, largely contained by the surrounding structures. But in reality, fire engulfs structures. Cities burn in sheets, not rivers. Fire eats air, creating windstorms, which feed and speed the fire. The Tokyo firebombing created walls of fire, ripping through closely packed, mostly wooden homes. In Dresden, a city where many of the buildings were reinforced with concrete, the Allied firestorm still destroyed over half the structures in the city with hurricane-speed winds.

Rather than seeing civilians running away down streets and hiding around protected corners, audiences should have seen them facing ever-growing, shifting, enveloping tsunamis of fire once the first few streets were lit. Rather than Cersei watching ribbons of flame from the distance, she should have seen whole neighborhoods swallowed up progressively. The ignition of wildfire would have only exacerbated this trend.

For this reason alone, it seems incomprehensible that Dany would unleash this holocaust in an area where her own troops were present – or that her soldiers would have any chance at a protected route of retreat. Historically, the strategic bombing of civilians from the air is not a method used in areas where ground troops are already engaging the enemy on foot – for good reason. Dany’s willingness to sacrifice her own remaining men to an indiscriminate firestorm – not her willingness to punish civilians, an act often undertaken during the siege of medieval cities – is actually the best indicator that she was acting irrationally. That the showrunners allowed us to believe that a large portion of her military survived the siege only underscores the cinematic sleight of hand at play.

Fire Kills Loudly and Slowly. Through a number of cinematic choices, the creators of “The Bells” also led audiences to think that death by firebombing is quicker, less painful, less terrifying and less certain than it actually would be.

In real life, a city under incendiary siege is a noisy place. Survivors of the firebombings of Dresden and Tokyo refer back above all to the screaming. Of course, there were panicked shouts and screams of fear in King’s Landing last week, but we did not hear the shrieks of the dying, as the showrunners chose to include in previous episodes.

Think of the screams of Mirri Maz Dur in Season One, or the cries of Shireen Barratheon in Season Five: the sounds of only one person at a time dying slowly by fire. When the Sept fell in Season Six, only a handful of political elites and surrounding civilians died in the resulting blaze, but their shrieks could be heard by King Tommen from his window at the Red Keep. Multiply that by tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians burning slowly to death in ongoing waves – what Cersei should have been listening to from the same window – and suddenly the episode we saw becomes eerily, unjustifiably quiet.

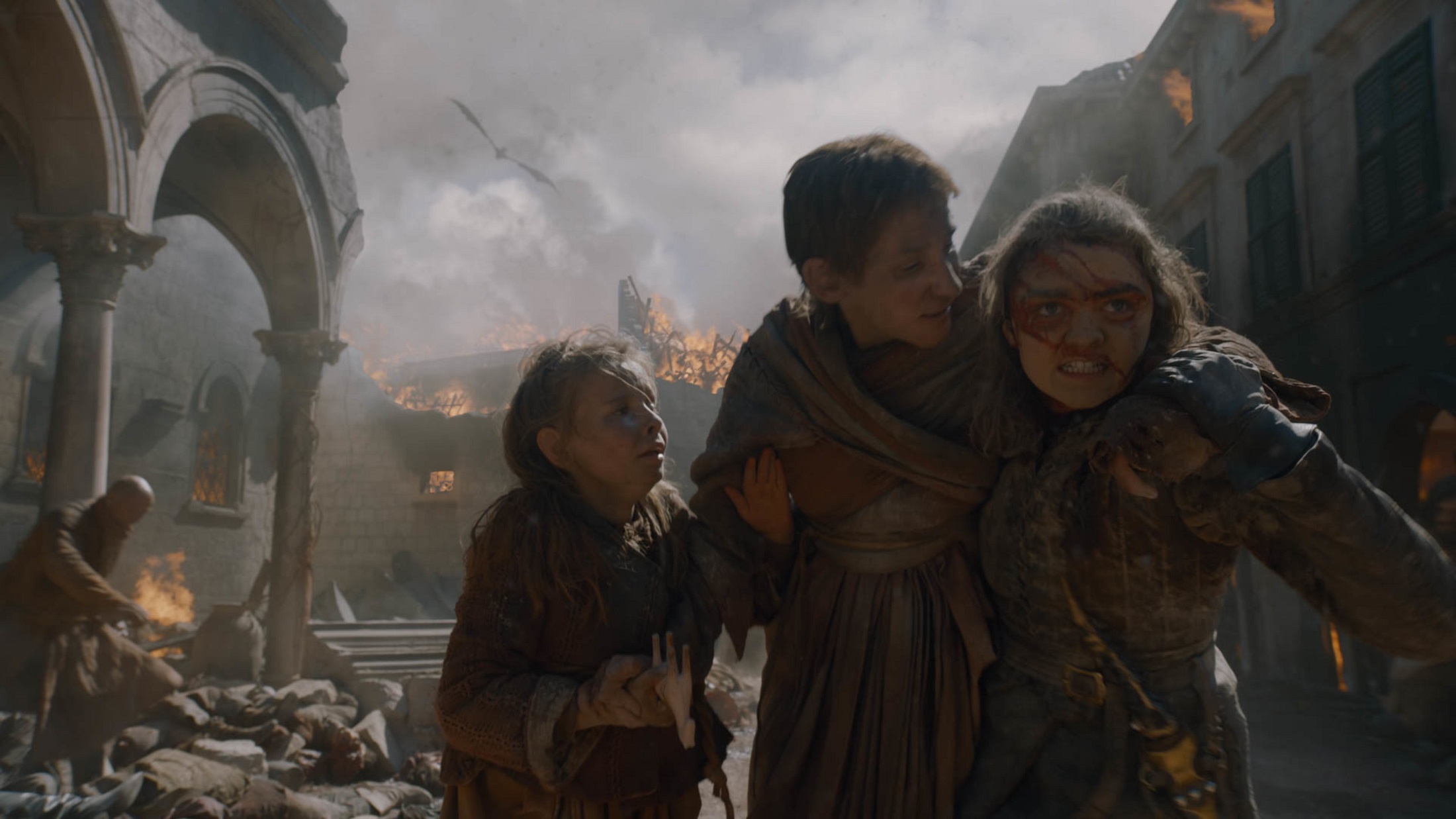

Visually, instead of choosing to portray fire’s lethal heat effects, and the full fury of their humanitarian consequences, the showrunners instead gave us primarily fast-killing blast effects. We see civilians overrun by bursts of flame and incinerated quickly and soundlessly – disappearing from sight into the flame, instead of convulsing before our eyes. We see civilians panicking and running from the fire, but we do not see mothers running away while listening as the babies on their backs actually catch fire and begin burning alive. We do not see people pile up in desperation at the end of city blocks as the flames overtake them.

To be fair, audiences were permitted to see the aftermath of death by fire: charred bodies appropriately reminiscent of images from the aftermath of Dresden, Tokyo and the countless other Asian and European cities targeted from the air in that period. But we are allow to imagine the inhabitants of King’s Landing died quickly, their corpses blackening in the aftermath. Just as we do not hear them, we do not see civilians slowly burning.

We also do not see civilians suffocate. In real firebombing campaigns of the 1940s, many civilians took shelter in cellars or other structures. But the heat of an inferno sucks away oxygen, dooming even those who escape the flames. In World War II, families were found huddled in blast shelters after suffocating together – a lingering death which can take up to three minutes.

Instead of capturing this reality, “The Bells” portrays interiors as vulnerable primarily to demolition and explosive violence. Civilians are seen sheltering inside buildings from the flames and melee. Cersei and Jaime find temporary respite in the catacombs. When Arya encourages a group to flee instead of sheltering in place, they are quickly killed, suggesting they would have been safer inside. In reality, they would likely have traded one death for another. The Lannister twins would likely have asphyxiated long before being buried alive.

As Tyrion says, “I do not want to hear the sound of children screaming as they burn alive.” Perhaps, the showrunners decided, audiences would also not wish to hear that sound. It is, as Qyburn reminds us, “not pleasant.” Yet by sanitizing the sound of the siege, by sanitizing the sight of it, by limiting its complexity, the showrunners dulled audiences’ senses to the reality of firebombing. By making the intolerable slightly more tolerable, they deadened our understanding of what massacre by air truly entails.

Firebombing Civilians is Strategically Ineffective. Though Dany may yet atone for her sins, by all appearances thus far the following episode depicts a successful claim to the throne, her army victorious, the remaining inhabitants (and her own people) cowed. Yet in the real world, there is no instance where a firebombing campaign yielded the result sought by its perpetrator – and often, it has yielded retaliation in kind.

Strategic bombing proponents in World War II believed terrorizing civilians from the air would induce surrender. But even the most oft-cited argument – that the atomic bomb forced a Japanese surrender – is historically disputed. The Hiroshima bombing took place on August 6th, 1945, but for three days the Japanese continued to refuse surrender and did not even meet to discuss the bombing. What convinced Japan to surrender was a different event occurring days later: Stalin entered the war, invading Japan from the north. Burning civilians with nuclear fire was little more effective than using regular incendiary bombs.

Which is to say, ineffective: there is no case in history where conventional firebombing produced the desired effect. When Nazi Germany tried it against Britain between 1941-1940, hoping to shock British civilians into demanding surrender, the Blitz only galvanized Brits and made them blood-hungry. Yet the British firebombing of German cities was equally counter-productive: German industrial production went up the more ordnance Britain dropped, and the age range for men and boys enlisting in the Wehrmacht expanded. Firebombing civilians has domestic blowback effects as well. In Vietnam, the use of napalm and carpet-bombing galvanized the peace movement at home and delegitimized the war. Recent use in Syria has led to renewed international efforts to more comprehensively outlaw incendiary weapons.

If the Game of Thrones finale is at all true to life, history will punish Dany for her crimes. Yet just as the show produced a devastatingly sanitized depiction of incendiary warfare, it is equally plausible that tonight’s finale will portray saturation bombing as an effective way to bolster a ruler’s legitimate claim to the throne. This would be a dangerously unrealistic portrayal of the political consequences of indiscriminate air power.

Why It Matters. It is now well known by social scientists that pop culture influences attitudes about real-world events. Audiences easily learn false lessons about history and causation through narrative storytelling loosely based on historical analogy. Depictions of political violence can sensitize or desensitize. They can influence political beliefs and public opinion. The messages audiences take from a show like Game of Thrones have political consequences.

While fans were obsessing over whether Dany had gone mad or whether Arya’s horse symbolized death or peace, the Trump Administration quietly began inching closer toward war with Iran. US public opinion polls have already been fielded testing American support for a saturation bombing strike on an Iranian civilian city in the event that the US finds itself in an intractable ground war unable to induce a surrender.

Pop culture can convey cautionary tales, and Game of Thrones has often done so. But the most popular show in history, known for its soberingly grisly portrayals of political violence, just whitewashed the implications of firebombing a civilian population. In so doing, it missed its chance to show American how terrible such an act would be for civilians on the other side and – if the enemy retaliated in kind – here at home.

[cross-posted at Duck of Minerva]