The War Poet and The Utility of Stoicism

“To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric…”

Theodor W. Adorno (1)

An image is worth a thousand words, but a thousand words often create their own images. Poetry has long been an important cultural form of bearing witness to tragedy and shaping our understanding of historical events. The poetry produced during and after World War I brims with cynicism and exhaustion and has always haunted me. While I was an undergrad at American University studying peace and conflict resolution, I picked up a text that had been assigned in a friend’s class: Against Forgetting, an anthology of twentieth century poetry of witness. From Latin America to Russia, the Holocaust and Palestine, this collection is a tribute to the human desire to build beauty out of pain.

Why would we want to make genocide beautiful? Is it because of a Judeo European Christian notion of suffering that purifies the soul? Romantic poet and illustrator William Blake was famous for his depictions of the suffering of the biblical Job. No, let me posit that is not at all the goal. It is the survival of trauma that we strive to make beautiful.

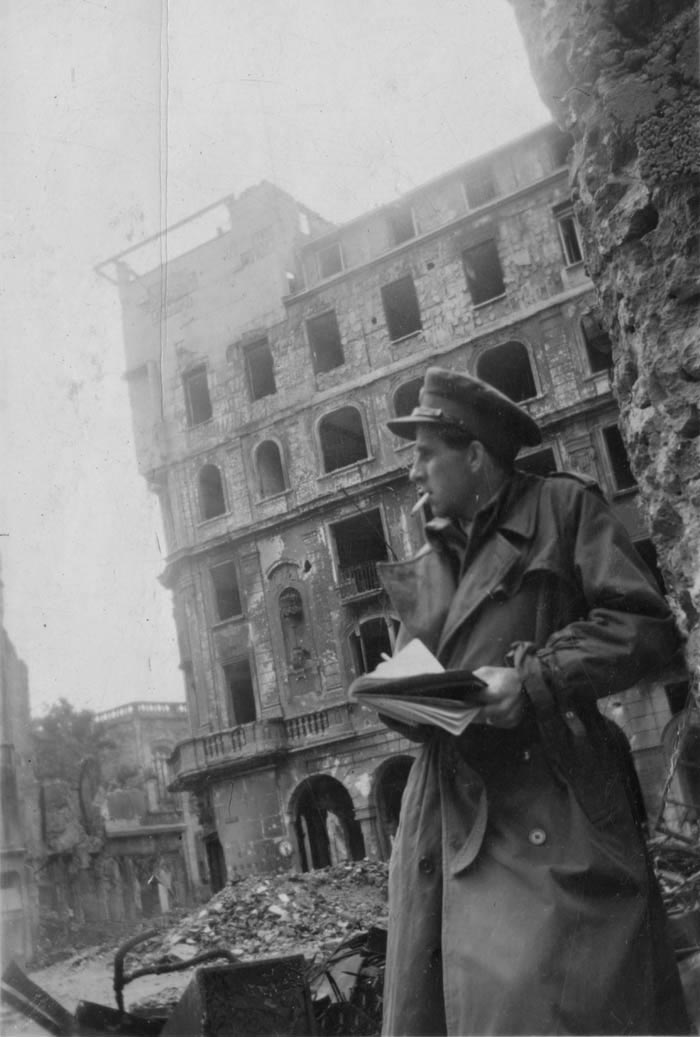

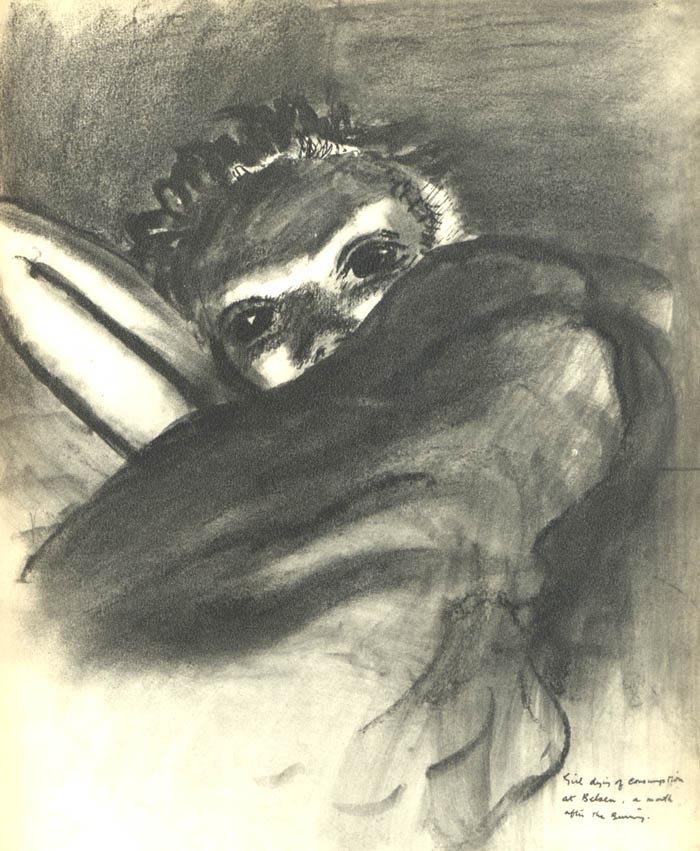

One of my favorite early 20th century writers, Mervyn Peake, struggled with his role as a secondary witness of human suffering and his attempts to capture it through text. In 1945, Peake became a war artist for the British weekly magazine The Leader. His commissions took him to German concentration camp of Bergen Belsen. He produced several poems from that time and a number of illustrations. Throughout his witnessing, he could never shake a feeling of detachment. Literary critic RW Malsen describes this in the introduction to Peake’s Collected Poems (emphasis mine):

But failing to connect with war and its victims was as horrifying a prospect for Peake as being possessed by them. His famous poem “The Consumptive. Belsen 1945” expresses shock at his own callous reaction to a dying girl he saw in the hospital for concentration camp inmates at Bergen-Belsen. In her face he notes the seeds of a ‘great painting’, and as he mentally nurtures these seeds he finds himself unable to respond as he should to the girl’s suffering. Filled with remorse, he promises in the penultimate line that her dying “shall not be betrayed”, presumably by being transformed into a work of art. Yet by then the work of art has already come into being: it is the poem we just read. (2)

I wonder if perhaps personal detachment for a secondary witness of atrocity is the only way anyone can properly communicate to the rest of the world what they have seen. A survivor obviously cannot be personally detached from their own suffering and if they do choose to put their experience into words it is a process that is as much about personal identity as it is about truth telling. Whatever stoicism the poet or artist adopts in the moment of witness or in the creation of images and text, the experience may still weigh heavily on them. The enormity of the darkness Peake saw would influence his writings and sketches for the rest of his career, even touching his illustrations for Alice in Wonderland. His magnum opus, the Gormenghast novels, are also filled with pieces from the war.

Theodor Adorno is said to have reconsidered the quote that I use above, on the “barbarism” of Auschwitz poetry. However he meant it in the moment, he is correct. To engage in a lyrical depiction of the inhumanity of genocide and war through text or image is to engage with that inhumanity. The only way we can overcome that obstacle is to include the victim and/or survivor as an active subject, not object. No matter who takes the pen or the paintbrush, the narrator of the story must always be them.

Further Reading:

Art After Auschwitz: The Problem With Depicting The Holocaust, Ysabelle Cheung

Gaza: Poetry After Auschwitz, Hamid Dabashi

Footnotes

- Adorno, Theodor W. Prisms. 1st ed. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1983.

- Peake, Mervyn, and R. W Maslen. Collected Poems. Manchester: FyfieldBooks, 2008.