Keep Mexico Weird!

A few brief thoughts on Mexico, and especially misperceptions of Mexico that seem common in the United States, but that particularly appear to animate Trump’s thinking.

- Mexico has 119 million (127 million according to World Bank data) people, making it the 11th most populous country in the world.

- Mexico’s PPP adjusted GDP is $2.193 trillion, making it the world’s 11th largest economy. Countries with smaller economies include Italy, South Korea, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Australia, et al. Per capita is $18857, putting Mexico firmly into the range of middle-income countries; on a per capita basis, Mexico would be the poorest large country in the EU, but on average Mexicans are wealthier than Chinese.

- Mexico’s GINI coefficient (to the extent this is a useful metric) is far from good, at 48.2, but isn’t much higher than that of China, and is below that of Brazil.

- Adult literacy in Mexico is 93%, behind Russia, slightly behind China, ahead of Brazil, and way ahead of India.

- Mexico’s Democracy Index score is 6.47, making it a “flawed democracy.” In comparison, this would put Mexico at the bottom of the EU and behind Brazil, but ahead of such countries as Ukraine and Georgia.

Nothing staggering here. Mexico is a really big middle income country, which makes it one of the world’s largest economies in aggregate. The population is relatively well-educated. Inequality is high, although this is exacerbated by stark geographic differences across the Mexico (big, diverse countries will generally have significant inequality).

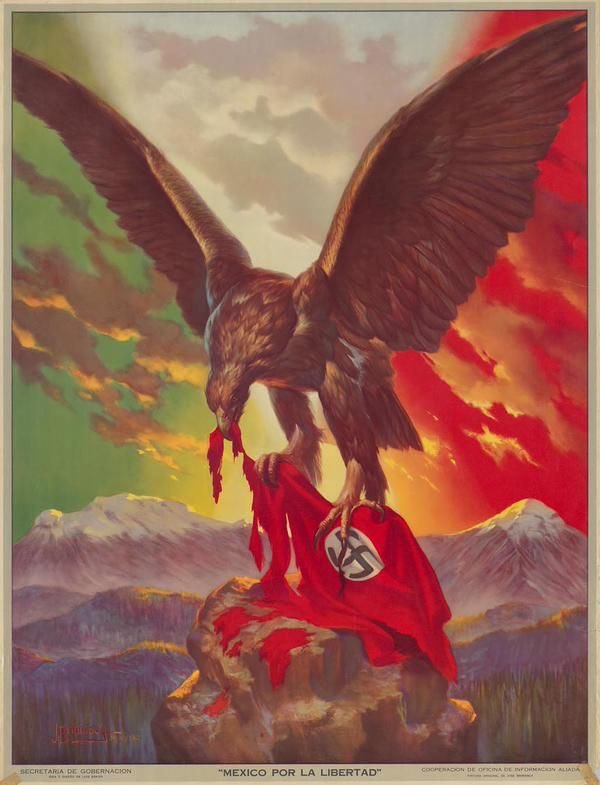

Where Mexico stands out is in foreign relations. Despite having an economic profile broadly similar (in overall heft) to the BRICS, Mexico has made no substantial effort to re-write the rules of the international economic order. Mexico is not part of NATO, despite participating in World War II from May 1942. Mexico has observer status in the Non-Aligned Movement, and has never been regarded as a leader of international organizations outside of the Americas. Even in the OAS, Mexico has only rarely wielded its economic and demographic heft to steer the organization in preferred directions.

This low profile extends to the military sphere. Mexico devotes .677% of its GDP to defense, which is…. really, really, really low. Military expenditure as part of government expenditure is 2.3%, which is also really, really low; less than half that of Brazil, and would be in the bottom rung (though not the absolute bottom) of NATO. In terms of equipment, the Mexican armed forces are severely undercapitalized. The fighter fleet of the Mexican Air Force (formally part of the Mexican Army [ed.- yay!]), consists of three F-5s. Three. The primary combat vessels of the Mexican Navy are mostly in excess of fifty years old, and include veterans of the Second World War. The primary military tasks of the Mexican armed forces are internal; fighting insurgents, and managing (in various ways) the drug trade. Mexico does not participate widely in UN peacekeeping missions; in 2016, it deployed a total of 23 personnel abroad. Mexico does not normally make substantial military contributions to regional multilateral operations, such as Haitian earthquake relief.

So if you want to identify an area in which Mexico is really weird, look no further. Mexico stands out even in comparison to Canada, which despite having a quarter of the population and a smaller economy, manages to spend twice as much on defense in raw, non-PPP adjusted terms. It stands out in contrast to other Latin American countries of similar economic and demographic stature, such as Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, or Brazil.

The explanation for Mexico’s weirdness seems simple; the overwhelming power of the United States effectively dictates Mexican national security policy. Mexico cannot hope to build a military capable of resisting the United States, much less protecting its emigrant populations or recovering lost territories. At the same time, no state other than the US can plausibly threaten Mexico’s security. Consequently, Mexico doesn’t face any very serious choices regarding national security policy; it can afford to have a very small defense budget and a non-activist foreign policy. This policy pays dividends insofar as it allows Mexico to allocate financial resources more efficiently than otherwise, to avoid costly entanglements, and (not least) to avoid some of the civil-military difficulties that have afflicted other Latin American countries.

As an explanation for Mexican security policy, that’s fine as far as it goes, but it only goes so far. There are plenty of countries in positions structurally similar to that of Mexico that do not make the same choice. As noted, Canada has historically adopted a much more activist military and foreign policy (explainable by Canada’s position within the Anglosphere and the Atlantic community, but still). Ukraine and Poland have not adopted “Mexican” strategies with respect to Russia, instead preferring internal and external balancing. Vietnam has constructed its security policy around measured resistance to China, rather than accommodation. Indeed, for the first hundred years of its existence Mexican security policy assumed (on and off, to be sure) an antagonistic United States. Brazil and Argentina also rely on implicit and explicit security guarantees from the United States, but carry out much more activist foreign and military policies than Mexico.

It is better to think of Mexico’s accommodationist foreign policy as a choice, rather than as a structural dictate. It is almost certainly a good choice; antagonism would cost more and invite more extensive US intervention, internal balancing (military buildup) would cost a lot more, external balancing (alliance with foreign powers) is extremely difficult on the multilateral side and not all that productive even in bilateral terms. But Mexico is surely large enough, and wealthy enough, to consider alternative choices.

Mexico’s accommodationist strategy also places some obligations (mostly implicit) on the United States. These include (relatively) decent treatment of the Mexican diaspora, an end to efforts to chip away at Mexico’s territory, a minimum of active subversion of the Mexican government, a degree of respect for Mexican sovereignty, and a degree of protection against the military or subversive ends of foreign powers. As long as these obligations are met (in broad terms), the United States gets a deal; it does not have to worry, at all, about the large, wealthy, potentially powerful country with latent but compelling irredentist claims along its southern border.

That’s a pretty good deal.

If I were in a senior policymaking position in the United States government, one of my central objectives would be to keep Mexican foreign and security policy “weird.” Mexico can afford to expend a much greater portion of its economy on defense; it can easily undertake a much more activist foreign policy. Mexico can afford a lot of Russian Su-27s and MiG-29s, or Saab Gripens, or Eurofighter Typhoons, or Chengdu J-10s. It can afford to upgrade its navy with submarines and modern surface warfare vessels, including missile-armed patrol boats that would give the USN headaches. It can afford to suspend or modify a wide range of cooperative security programs with the United States.

Mexico probably won’t do any of these things, partially because of inertia, and partially because balancing would require a major resource allocation. But then previous US Presidents have tended to shy away from hinting at pogroms against the Mexican diaspora, or at suggesting that the US military will intervene directly in Mexico’s sovereign territory.