The Cubs Must Not Win (IV)

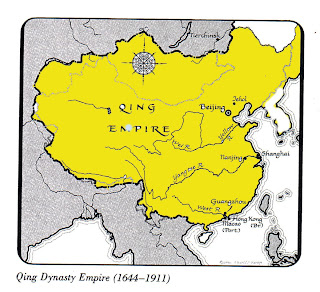

When last the Cubs won the World Series, the Qing ruled China:

The tribal peoples of northeast Asia had been of concern to the Chinese Empire well prior to the 17th century. In the 13th century, the Mongols had descended upon China and created the Yuan Dynasty, only to be chased out less than a hundred years later. The Yuan were replaced by the native Ming Dynasty, which reinforced the northern defenses and forced many the tribes into vassalage. In 1583 the Jurchen chieftain Nurhaci, whose father and grandfather had died in service to the Ming emperor, began to consolidate the northern tribes under a new system of military organization. Nurhaci also carried out military campaigns against the Mongols, gaining their respect and a degree of allegiance. In 1612 he renamed his clan Aisin Gioro, and in 1616 founded the Later Jin Dynasty, centered around the town of Mukden. Wars against the Koreans, Mongols, Ming, and other northern tribes expanded the Jin until Nurhaci’s death in 1626. His son and successor Huang Taiji further expanded the Jin, renaming in Qing and mandating that the Jurchen people would henceforth be known as the Manchu people.

The tribal peoples of northeast Asia had been of concern to the Chinese Empire well prior to the 17th century. In the 13th century, the Mongols had descended upon China and created the Yuan Dynasty, only to be chased out less than a hundred years later. The Yuan were replaced by the native Ming Dynasty, which reinforced the northern defenses and forced many the tribes into vassalage. In 1583 the Jurchen chieftain Nurhaci, whose father and grandfather had died in service to the Ming emperor, began to consolidate the northern tribes under a new system of military organization. Nurhaci also carried out military campaigns against the Mongols, gaining their respect and a degree of allegiance. In 1612 he renamed his clan Aisin Gioro, and in 1616 founded the Later Jin Dynasty, centered around the town of Mukden. Wars against the Koreans, Mongols, Ming, and other northern tribes expanded the Jin until Nurhaci’s death in 1626. His son and successor Huang Taiji further expanded the Jin, renaming in Qing and mandating that the Jurchen people would henceforth be known as the Manchu people.

The rise of the Qing corresponded with the decline of the Ming. Internal disputes and a major peasant rebellion had weakened the aging dynasty such that the Qing were able to press successfully on its northern territories. A series of victories in the early 1640s led to the conquest of the imperial capitol at Beijing in 1644. The Manchus, uncharacteristically for foreign invaders, showed immense respect for Chinese imperial forms and styled themselves the direct inheritors of Ming imperial rule. Over the next thirty years the Manchus, under the rule of Emperor Kangxi from 1661, would destroy the remnants of the Ming and subjugate various other opponents, including the Mongols. The last serious resistance on the part of Ming loyalists would be conducted on the island of Formosa, which had previously been occupied by Dutch traders and non-Han tribesmen. The Qing extinguished this resistance in 1683, occupying and annexing, for the first time, the island to the Chinese Empire.

Emperor Kangxi served from 1661 until his death in 1723. His grandson, the Qianlong Emperor, served from 1735 until his abdication in 1795. Although the Qianlong Emperor’s reign is remembered both as a time of plenty and an age of significant cultural achievement, by the end some strains were beginning to show. Pressure inside and outside China began to increase, as corruption rose and the military threat of encroaching European powers grew. The Opium Wars, an unfavorable balance of trade, the Taiping Rebellion (led by a man who styled himself the younger brother of Jesus Christ), and an increase in nationalist (and anti-Manchu) feeling significantly weakened the dynasty. Efforts at reform were bitterly resisted by the Manchu aristocracy, personified from 1861 by the Empress Dowager Cixi. Cixi dominated Chinese imperial politics until her death in 1908. Shortly before dying, she installed Puyi, not yet three years of age, as Emperor of China.

The Qing Dynasty survived Cixi by three years. Puyi was allowed to remain in the Forbidden City in Beijing until 1924, and enjoyed a very brief restoration in 1917. Eight years after his expulsion from the Forbidden City, Puyi became emperor of the Japanese puppet state of Machukuo, built around territory seized by Japan from China in 1931. Puyi held virtually no real power, and what supporters he had were steadily replaced or undermined by the Japanese. Manchukuo was instrumental in the Japanese Fugu Plan, a rather odd effort to attract Jews (and their presumed innate ability to make money and dominate the minds of men) from Nazi dominated parts of Europe to the Far East. In any case, the Japanese effort in World War II went poorly, and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 brought Manchukuo to an end. Puyi was captured by the Red Army and eventually extradited to the People’s Republic of China.

The Qing Dynasty survived Cixi by three years. Puyi was allowed to remain in the Forbidden City in Beijing until 1924, and enjoyed a very brief restoration in 1917. Eight years after his expulsion from the Forbidden City, Puyi became emperor of the Japanese puppet state of Machukuo, built around territory seized by Japan from China in 1931. Puyi held virtually no real power, and what supporters he had were steadily replaced or undermined by the Japanese. Manchukuo was instrumental in the Japanese Fugu Plan, a rather odd effort to attract Jews (and their presumed innate ability to make money and dominate the minds of men) from Nazi dominated parts of Europe to the Far East. In any case, the Japanese effort in World War II went poorly, and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 brought Manchukuo to an end. Puyi was captured by the Red Army and eventually extradited to the People’s Republic of China.

After undergoing re-education (immortalized in Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor) Puyi lived in Beijing until his death without issue in 1967. The imperial line passed either to Puyi’s cousin Yuyan, who endured two long terms of imprisonment before his final release in 1979, or to Puyi’s brother Pujie, who had a similar prison career. Although Yuyan became the subject of a British documentary, the evidence seems to favor Pujie, who died in 1994. The line then passed to Jin Youzhi, Pujie’s half-brother, who died in 2015. The most plausible current heir is Jin Yuzhang, son of Jin Youzhi. Mr. Jin, 74 years, is a retired Beijing district-government vice-director. Mr. Jin spent time during the 1960s as a Red Guard, and lived for a while with Puyi after the latter’s return to Beijing.

After undergoing re-education (immortalized in Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor) Puyi lived in Beijing until his death without issue in 1967. The imperial line passed either to Puyi’s cousin Yuyan, who endured two long terms of imprisonment before his final release in 1979, or to Puyi’s brother Pujie, who had a similar prison career. Although Yuyan became the subject of a British documentary, the evidence seems to favor Pujie, who died in 1994. The line then passed to Jin Youzhi, Pujie’s half-brother, who died in 2015. The most plausible current heir is Jin Yuzhang, son of Jin Youzhi. Mr. Jin, 74 years, is a retired Beijing district-government vice-director. Mr. Jin spent time during the 1960s as a Red Guard, and lived for a while with Puyi after the latter’s return to Beijing.

Prospects for restoration seem quite grim. Very little sentiment for a return to the monarchy exists in China, and it is unlikely that, in the unlikely event of a monarchical restoration, the Manchu Qings would be selected for imperial honor. The Manchu ethnic minority has been substantially assimilated by the Han Chinese, making a return to the throne in an independent Manchukuo equally unlikely.