How to Excuse Torture

The following is a guest post by William L. d’Ambruoso, Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Washington.

It is bizarre – or, if it isn’t, it should be – that the leading members of one of two major political parties in one of the world’s most firmly established liberal democracies refuse to rule out coercive interrogation against terrorist detainees. Even stranger, the frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination, Donald Trump, has not yet suffered politically for saying that he’d “bring back waterboarding and…a hell of a lot worse…” If anything, he seems to have benefited.

Whether they plan to use it frequently or rarely, Republicans agree on how to excuse torture: by comparing this country’s behavior favorably with that of its enemies. This approach echoes the justifications offered by previous administrations. Then and now, these comparisons are misleading and irrelevant, and should not be a basis for another era of liberal-democratic torture.

Cruelty, by nature, can always be worse. A torturer can always find an example of something more horrible than what he is doing. According to Mr. Trump, “[W]aterboarding is peanuts compared to what they’d do to us, what they’re doing to us, what they did to James Foley when they chopped off his head.” Mr. Trump has repeatedly promised to go further than waterboarding. As long as he stays short of the horrors of beheading on the cruelty scale, he figures that he’s taking the moral high road.

Memories of these enabling comparisons in the George W. Bush administration are recent enough, but in case they are not, former administration officials still occasionally take to the airwaves to juxtapose the war on terror’s “enhanced interrogation techniques” against the tactics of the enemy. Torture, as recently defined by Dick Cheney, “is an American citizen on a cell phone making a last call to his four young daughters shortly before he burns to death in the upper levels of the Trade Center in New York City on 9/11. There’s this notion that somehow there’s moral equivalence between what the terrorists and what we do. And that’s absolutely not true.”

Jeb Bush made essentially the same point last summer: “There’s a difference between enhanced interrogation techniques and torture. America doesn’t torture.” In New Hampshire, Ted Cruz used the Bush administration’s “vanishingly narrow” definition of torture to exclude waterboarding. “Civilized nations” don’t torture, according to Mr. Cruz, but they can use “enhanced interrogations,” including waterboarding, in emergencies. Torture is something other people do.

Unsurprisingly, Mr. Trump has promised to be the harshest torturer of the bunch. But even as he claims that a Trump administration would do “whatever it takes,” he still uses euphemistic “enhanced interrogation” language to sell the point.

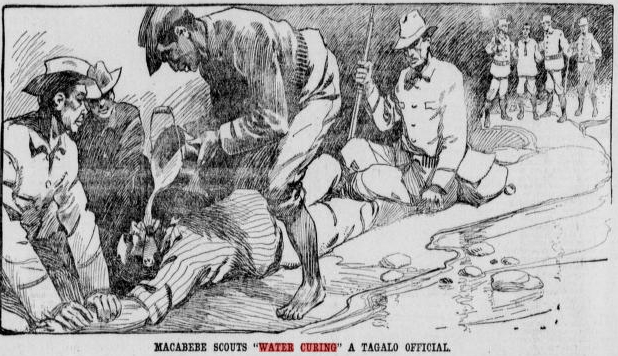

America’s use of favorable comparisons to excuse torture has deeper roots. In the Philippine-American War, General Fred Funston claimed that when Filipino soldiers under his command used the “water cure” (a method similar to waterboarding) against insurgents, they “were merely repaying the insurgents for worse treatment received by them in the past.” President Theodore Roosevelt also downplayed the water cure as a “mild torture,” claiming, “Nobody was seriously damaged, whereas the Filipinos had inflicted incredible tortures on our own people.” To his credit, Mr. Roosevelt still maintained that violators should be held to “sharp account,” and some (though not all) were prosecuted.

What most of today’s leading Republicans aren’t divulging is that “clean” techniques like waterboarding are designed to look and sound milder than they are. As Reed College political scientist Darius Rejali argues, liberal democracies, with their human rights laws and free presses, have been torture innovators, pioneering or adapting clean techniques like waterboarding (as well as stress positions, sleep deprivation, etc.) to avoid censure and prosecution. We should not be fooled. Journalists and even skeptical conservative talk show hosts have admitted that waterboarding is torture when faced with the cloth and pitcher.

Comparisons to the enemy are not just misleading, however; they are also irrelevant. Senator John McCain states the matter well: “[Al-Qaeda] has no respect for human life or human rights. They don’t deserve our sympathy. But this isn’t about who they are. This is about who we are. These are the values that distinguish us from our enemies.”

Sadly, advocates of “enhanced interrogation” may have shifted the debate in their favor. Not only did Mr. Trump win the New Hampshire primary handily; he has probably received as much admonishment for crass language as he has for his disregard for human rights. Fifteen years ago, Mr. Trump’s support for torture would have been outrageous; it should be outrageous now. We should strive for a society in which politicians who endorse torture pay a steep political price.