The charms of baseball

Last night’s game highlighted one of baseball’s most striking features, which is the completely different quality the game takes on in high stakes situations. Most of the time baseball is boring. I don’t mean that as a criticism: The typical regular season game means so little that it’s possible to half-watch it in a comfortable detached way, even when you’re actually in stands. This makes it quite different from the way in which one (and by one I mean me) experiences football or basketball or hockey, in which something is always happening or at least on the verge of happening.

Baseball consists largely of nothing happening: it’s three hours of standing around punctuated by about two minutes of combined action. (Yes I’m ignoring the subtle confrontation that is every pitch sequence to every batter. The point is during a regular season game you have to be either 12 years old or a grown-up fan of truly geeky intensity to get much catharsis from that confrontation, when it’s the third inning of a mid-June game between a couple of .500ish teams that probably aren’t going anywhere this year).

This quality is captured well by John Updike, in my all-time favorite piece of sports writing, his essay on Ted Williams’ last game:

For me, Williams is the classic ballplayer of the game on a hot August weekday, before a small crowd, when the only thing at stake is the tissue-thin difference between a thing done well and a thing done ill. Baseball is a game of the long season, of relentless and gradual averaging-out. Irrelevance—since the reference point of most individual games is remote and statistical—always threatens its interest, which can be maintained not by the occasional heroics that sportswriters feed upon but by players who always care; who care, that is to say, about themselves and their art.

The players — well most of them anyway; you can leave the room now, Mr. Ivie — always care, but we don’t have to, or not nearly as much — which is why a baseball game is in its own way a perfect accompaniment (ideally through a radio) to a lazy summer evening.

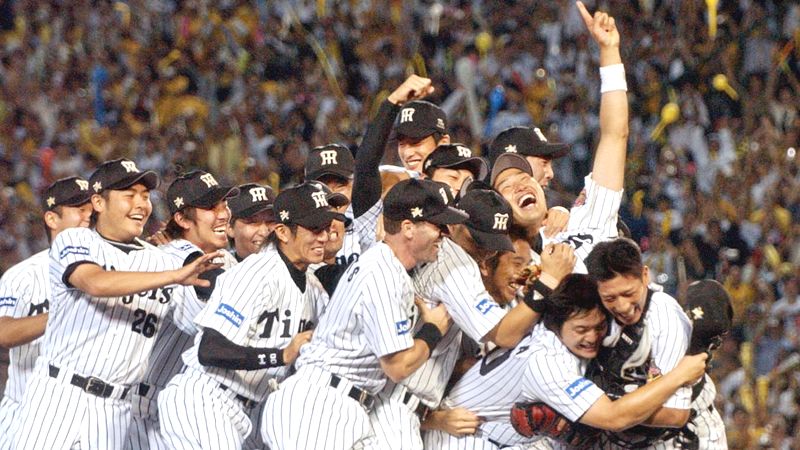

But in the heat of a pennant race, or in the post-season, all this changes, gradually at first, but then with startling suddenness, so that the game is transformed for all but the most casual fan into an experience of passionate intensity that equals or exceeds anything in sports. Last night’s game at Yankee Stadium, in which for the last two hours the entire season for both teams seemed to hang in the balance on almost every pitch, was a perfect illustration of how the very same game can be transformed from a pleasant background murmur into the most relentlessly excruciating of sports. And the key to the remarkable intensity of that transformation is precisely that, 99 out of 100 times, nothing much is at stake.

This is not the sort of quality that lends itself to our 24/7 contemporary sports world of constant fake hype and manufactured excitement, which is why most of the time baseball seems in many ways an anachronistic sport. And that too is part of its charm.