Worst American Birthdays, Vol. 41

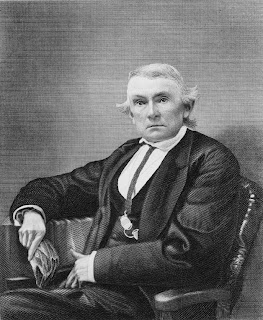

Nearly 200 years ago, on 11 February 1812, free white child named Alexander Hamilton Stephens was born on a nondescript Georgia farm.

Nearly 200 years ago, on 11 February 1812, free white child named Alexander Hamilton Stephens was born on a nondescript Georgia farm.

He was a frail, sickly boy whose weight never exceeded a hundred pounds, even as an adult. Born into slavery, a child like Stephens would have spent his life dropping seeds and gathering manure chips; as a part of the master race, however, even a common farmer’s son might look forward to a world beyond the cornrows. Stephens’ knowledge of the Bible — a book from which slavery’s advocates would draw affirmation and reassurance — earned him a scholarship to the University of Georgia, where he studied until his graduation in 1832.

After a successful career as a lawyer, Stephens served his white Georgian brethren as a member of the US House of Representatives from 1843 to 1859. A Whig by party affiliation, Stephens’ tenure in the Congress coincided with one of the most ferocious periods of American political history. In the wake of the Mexican War (which Stephens opposed along with most of his fellow Whigs), both major parties were eventually torn in half over the question of extending slavery into the new territories. Stephens, who by this point owned more than two dozen men and women, supported the rights of slaveholders to bring their property anywhere in the United States. Thus, he supported most of the 1850 compromise, which opened most of the western territories to slavery; he voted for the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which overturned the Missouri Compromise and turned the region into a gangland; and he celebrated the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which asserted that the Federal government could do nothing (short of a Constitutional amendment) to interfere with slavery.

Satisfied that white rights to human property had been secured forever, Stephens retired from the Senate in 1859. When Lincoln swept the free states in 1860 and won the presidency for the Republican party, Stephens — returning quickly to public life — failed to persuade most of his peers in Georgia from breaking away from the Union; unable to steer the hard core secessionists away from the cliff, he nevertheless decided to join them. On his 49th birthday, Alexander Stephens took the oath of office as the Vice President of the Confederate States of America.

A little over a month later, Stephens delivered an address in Savannah that came to be known as the “Cornerstone Speech.” Enumerating the differences between the confederacy and the United States, the Confederate vice president announced that the nation’s founders had been wrong to view slavery as a “necessary evil” and that believers in unversal human equality were mistaken. Instead, Stephens explained that black inferiority and subordination were merely the expression of a “great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” The Confederacy, therefore, lay closer to nature than any government in human history.

With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material — the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it, and by experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so. It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator. It is not for us to inquire into the wisdom of His ordinances, or to question them. For His own purposes, He has made one race to differ from another, as He has made “one star to differ from another star in glory.” The great objects of humanity are best attained when there is conformity to His laws and decrees, in the formation of governments as well as in all things else. Our confederacy is founded upon principles in strict conformity with these laws. This stone which was rejected by the first builders “is become the chief of the corner” — the real “corner-stone” — in our new edifice.

Though Stephens could not imagine any outcome but Southern victory, the Confederacy was obliterated within four years. After spending five months in prison, Stephens resumed his political career. In 1873, he returned to the Congress as a Democrat and served for nearly ten years in the House before ending his life with a brief stint in the Georgia governor’s office.

Although the cornerstone of Stephens’ ideal republic did not survive in the form of the Confederacy, he would have been pleased to know that within a decade after his passing, the principle of “negro” subordination had been reasserted throughout the land.