"A revolution but half-accomplished"

Reading part of an econ dissertation linked by Yglesias, I’m reminded Carl Schurz’s famous description of Reconstruction. In her project, University of Michigan graduate student Melinda Miller examines the post-civil war economic status of Cherokee freedmen and measures it against the livelihoods of emancipated slaves throughout the rest of the former Confederacy:

The Cherokee Nation, located in what is now the northeastern corner of Oklahoma, permitted the enslavement of people of African descent. After joining the Confederacy in 1861, the Cherokee Nation was forced during post-war negotiations to allow its former slaves to claim and improve any unused land in the Nation’s public domain. To examine this unique population of former slaves, I have digitized the entirety of the 1860 Cherokee Nation Slave Schedules and a 60 percent sample of the 1880 Cherokee Census. I find the racial gap in land ownership, farm size, and investment in long-term capital projects [was] smaller in the Cherokee Nation than in the southern United States.

The whole paper (available as a PDF here) is quite interesting. She notes, for example, that the more stable patterns of Cherokee land tenure allowed its freedmen to invest in agricultural projects — like fruit orchards — that were extremely lucrative compared with corn or cotton. More than half of all Cherokee freedmen earned income from fruit cultivation, whereas less than three percent of Southern blacks found themselves in a position to do so.

For a historian, though, the larger question remains whether the results of this “

For a historian, though, the larger question remains whether the results of this “exogamous exogenous variation” among the Cherokee could have been duplicated throughout the rest of the South. I don’t think it could have been. There’s no question that any morally just outcome to the Civil War would have included massive agrarian reform, including the total liquidation of the plantation economy and the redistribution of the region’s land without regard to race or previous condition of servitude. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 made some effort in this direction and — had it been applied to more than five states, and had it actually hacked apart the viable plantations lands that were largely restored to their previous owners — it might have worked some of the effects that Miller finds among the Cherokee.

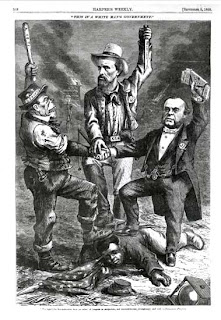

But very little decent land was actually conveyed to freedmen and poor whites, and after a decade the law was repealed — offering another piece of evidence to opponents of Reconstruction, who yowled constantly about the foolishness of government action on behalf of the oppressed. By that time, in any case, Northern Republicans and “New South” Democrats — most of whom were former Whigs and racial moderates — had reached an agreement that the reconstruction of the South did not require political, economic and social liberty for blacks. Within a decade, those moderates were forced aside by even more reactionary elements who reintroduced herrenvolk order throughout the South. If emancipated slaves had actually been offered a fair opportunity after the war to own the lands they’d worked for generations, the white reconquest would arguably have been bloodier than it actually turned out to be. That would certainly have been a war worth fighting, but it wasn’t a war that Northern whites were prepared to endorse.