Worst American Birthdays, vol. 26

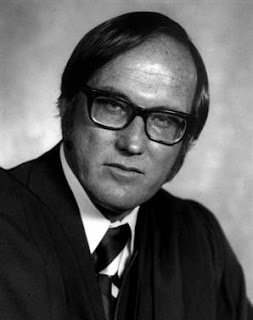

William Hubbs Rehnquist was flushed into the world 83 years ago today.

William Hubbs Rehnquist was flushed into the world 83 years ago today.

During his ascent toward the Supreme Court, where he would eventually serve nearly 20 years as Chief Justice, Rehnquist established himself as a vigorous defender of 19th century racial custom. While serving as a clerk for Associate Justice Robert Jackson in 1952, a youthful Rehnquist drafted an infamous, spritely memo in which he insisted that Plessy — the 1896 case validating the constitutionality of segregation laws — was “right and should be reaffirmed.” As he explained to Jackson,

in the long run it is the majority who will determine what the constitutional rights of the minority are. One hundred and fifty years of attempts on the part of this Court to protect minority rights of any kind — whether those of business, slaveholders, or Jehovah’s Witnesses — have been sloughed off, and crept silently to rest. If the present Court is unable to profit by this example it must be prepared to see its work fade in time, too, as embodying only the sentiments of a transient majority of nine men.

Rehnquist elaborated on this point in another memo the next year, when he informed the justice that “white people of the south don’t like the colored people,” and that the Court could only do so much to alleviate the burdens placed upon minority rights. (These observations, it should be recalled, came less than a decade after World War II had seemingly demonstrated the perils of racial majoritarianism. Then again, Rehnquist’s wartime duty was limited to stateside meteorology, and so his sensitivity to the war’s broader ideological meanings may not have been terribly well sharpened.)

Although Jackson and the eight other justices failed to accept his deference toward herrenvolk democracy, Rehnquist continued to fight the good fight as a private attorney in Phoenix. While the national civil rights movement pursued federal legislation with greater urgency, Rehnquist donated his time to “Operation Eagle Eye,” a voter-suppression effort organized by the state’s Republican Party. For several years, he and other GOP lawyers assembled themselves into flying squads that harassed south Phoenix voters — most of whom were African American and Latino — and challenged their credentials as they waited in line. Rehnquist’s goonery eventually helped earn him a position in the Nixon Justice Department and, before long, on the highest court in the land. Somewhat perversely, William Rehnquist was confirmed to the seat last occupied by John Harlan II, the grandson of Plessy’s lone dissenter and an important advocate for racial equality in his own tenure on the court.

In his 34 years on the bench, Rehnquist helped drag the court rightward, to such a degree that traditional judicial conservatives like John Paul Stevens eventually appeared liberal by comparison. He continued to take a dim view of individual (and especially minority) rights, interpreting the Equal Protection Clause in the sort of narrow terms that would have made his 19th century forebears proud. And in the Chief Justice’s waning years, the Rehnquist Court bequeathed to the nation the singular error known as the Bush Presidency, which — among its other constitutional sins — has presided over (arguably) the worst decline in civil rights since the second Cleveland administration.

All that said, we would be amiss in overlooking Rehnquist’s gift for music. At the annual 4th Circuit Judicial Conference, the Chief Justice used to lead friends and colleagues in rousing choruses of old-time American songs, including an enlightened ditty known as “Dixie.”