Columbus Day

Although Columbus Day has its roots in 19th century secular fantasy — specifically, an odd blend of Anglo-American nationalism and Italian-American ethnic pride — since the Nixon administration the second Monday in October has been set aside to acknowledge the accomplishments of one of mid-millennial Europe’s greatest religious fanatics.

Although Columbus Day has its roots in 19th century secular fantasy — specifically, an odd blend of Anglo-American nationalism and Italian-American ethnic pride — since the Nixon administration the second Monday in October has been set aside to acknowledge the accomplishments of one of mid-millennial Europe’s greatest religious fanatics.

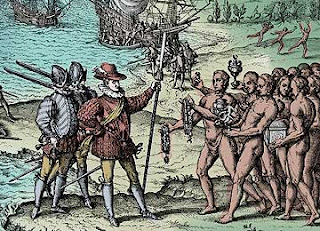

In his correspondence with Ferdinand and Isabella, “Columbus” (as his name was later anglicized) signed his name “christo ferens,” which literally means “Christ-bearer.” Based on his own readings of scripture, Columbus believed that the reconquista — Spain’s forced conversion and expulsion of Iberian Muslims and Jews in 1492 — marked the completion of Biblical prophecy. Moreover, Columbus believed in the wake of this glorious ethnic cleansing, Spain’s patronage of his voyages offered proof that he was to serve as a great evangelizing instrument on behalf of the Catholic faith. Personal aggrandizement aside, however, the “Christ-bearer” imagined that his voyages would serve much wider geopolitical ends. To the degree that Columbus himself would earn a tithe from the conquest of the Indies, he also encouraged the Spanish monarchy to devote the accumulated riches of the New World toward the recapture of Jerusalem.

For very good reasons, almost no one gives a shit about Columbus Day any more. On the other hand, if we were to think of Columbus as the continent’s original neoconservative gangster, the second Monday in October might become interesting again — particularly if we recall that after his third voyage, he was arrested and brought home in leg irons.