Worst American Birthdays, vol. XVII

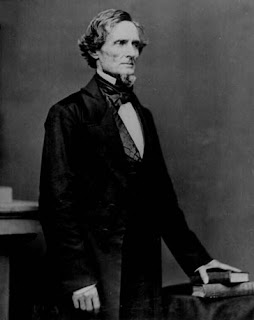

One of the great injustices in Curtis Mayfield’s short life was that he was forced by circumstance to share his birthday with Jefferson Davis, the former Mississippi Congressman and Senator who served as President of the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865.

One of the great injustices in Curtis Mayfield’s short life was that he was forced by circumstance to share his birthday with Jefferson Davis, the former Mississippi Congressman and Senator who served as President of the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865.

Born to modest means in Kentucky, Davis married well — first to the daughter of General (and future President) Zachary Taylor, then (after his first wife died of malaria) to the daughter of a wealthy cotton planter, from whom Davis would acquire considerable wealth and social standing. A graduate of West Point, Davis fought in the American war against Mexico; after the war concluded, Davis strove to ensure that the beloved institution of slavery could be extended into the conquered lands. He was a determined opponent of the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California to the union as a free state, and while he continued to insist throughout that ominous decade that secession was inadvisable, he held these views only so long as he believed the Southern states could maintain the political hegemony they had enjoyed since the nation’s founding.

When it became clear to Davis and others that the “zealots” of the North would not guarantee slaveholders the Western lebensraum they believed necessary for the survival of “liberty,” they invented an array of legal and historical fables to justify the secession of eleven Southern states. Like most Southern elites, Davis believed slavery to be sanctioned by God. However, his views on slavery were more peripheral to his overall ideology than other Confederate leaders — including his Vice President Alexander Stephens, who believed slavery was the “cornerstone” of the Confederate nation. Ultimately, Davis’ rhetorical preference for an abstract “states’ rights” philosophy would provide later generations of Confederate apologists with a valuable alibi. They could point to Davis’ record as “evidence” that the Confederacy was not founded on racism and human bondage.

After his state voted to leave the union, Davis resigned his Senate position in January 1861, warning his colleagues that they should simply allow the Confederacy to live apart and in peace.

If you desire at this last moment to avert civil war, so be it; it is better so. If you will but allow us to separate from you peaceably, since we can not live peaceably together, to leave with the rights we had before we were united, since we can not enjoy them in the Union, then there are many relations which may still subsist between us, drawn from the associations of our struggles from the Revolutionary era to the present day, which may be beneficial to you as well as to us.

If you will not have it thus–if in the pride of power, if in contempt of reason, and reliance upon force, you say we shall not go, but shall remain as subjects to you–then, gentlemen of the North, a war is to be inaugurated the like of which men have not seen . . . .

Is there wisdom, is there patriotism in the land? If so, easy must be the solution of this question. If not, then Mississippi’s gallant sons will stand like a wall of fire around their State; and I go hence, not in hostility to you, but in love and allegiance to her, to take my place among her sons, be it for good or for evil.

Reluctantly, Davis accepted the office of presidency; his leadership was widely regarded at the time as uninspired and ineffective, with critics deriding him as an autocratic federalist. Critics insisted his military command was unwise. Nevertheless, by the time he went toe-up in 1889 Jefferson Davis was celebrated as an enduring hero of the Lost Cause. Today, commemorative statues of him are littered throughout the South, and several states acknowledge his birthday as a legal holiday. In 1978, a Mississippi Congressman named Trent Lott led a successful push to have political rights restored to Davis’ corpse, which has since elected not to exercise those rights.