Colfax Massacre

Today is the 134th anniversary of the massacre in Colfax, Louisiana, where white and black militias clashed in an Easter Sunday battle that left scores of blacks dead. According to a racist historical marker located at the site of the killings, the white victory “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

Today is the 134th anniversary of the massacre in Colfax, Louisiana, where white and black militias clashed in an Easter Sunday battle that left scores of blacks dead. According to a racist historical marker located at the site of the killings, the white victory “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

The roots of the massacre originated with the disputed elections of 1872, which produced rival claimants to the governorship as well as local offices throughout the state; as conservative whites labored to bring an end to Reconstruction and restore white rule, their candidates struggled for power against black and white Republicans backed by the US Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant. Parallel inaugural ceremonies were conducted on 14 January 1873, as two different governors asserted their authority. Political order throughout the state collapsed, and open, organized violence took its place. In Grant Parish, a newly-created majority black district located in central Louisiana, the contest for local offices of judge and sheriff led initially to the installation of white candidates. These “victors” were soon nudged aside, however, by a federal judge who ruled in favor of their black rivals (who probably won the election in the first place). When the officials took control of the courthouse, hundreds of black residents of the parish, fearing reprisals, took shelter at the courthouse as irregular white forces assembled across the countryside and converged on the town of Colfax.

As the Colfax Chronicle deceptively recounted the events in 1914,

The Negroes took over and rioted, rifled homes, and said they were going to kill all the white men and take their white women and start a new race. The Negroes then carried out rape, robbery and murder. They took white judge Rutland’s deceased son’s casket out of the judge’s home and threw it on the ground.

Alarm over the Negro’s action spread into the surrounding Parishes and 200 white men responded to the call for help. They demanded the Negroes give up the offices and records. The Negroes said no. The Negroes also threw up breastworks from trenches they dug around the courthouse. The whites told the Negroes to remove their women and children, which they did. Some Negroes went home due to the delay in fighting, just a standoff. Several days passed.

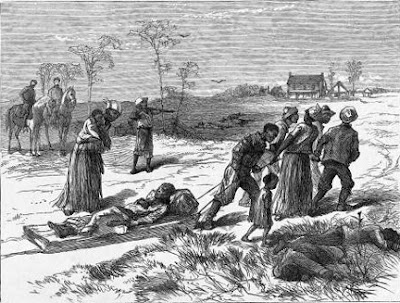

After a nearly two-week seige, on Easter 1873 the assembled white mob — led by former Confederate army officers — set fire to the courthouse. When armed blacks fired on the white paramilitary force, a four-hour battle commenced. By the end, three members of the White League had been killed while more than one hundred blacks died. Most of the deaths took place after the fighting had ceased as the White League forces shot, mutilated and dumped the bodies of their victims into the Red River.

Although federal charges were brought against nine Colfax conspirators under the 1870 Enforcement Act, the Supreme Court ruled in Cruikshank (1876) that the 14th Amendment — which the 1870 law was intended to uphold — applied only to state actions and did not apply to individuals.

With the Supreme Court’s stamp of approval, the rout was on. In the wake of the violence at Colfax, white paramilitary forces assembled throughout the state and across the South with the aim of ending “Negro domination” once and for all. In 1874, Louisiana gubernatorial candidate John McEnery insisted that “we shall carry the next election, if we have to ride saddle-deep in blood to do it.” Although his boast was not fulfilled, the violence in Louisiana continued. Republicans held control for three more years until the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877.

(cross-posted at Axis of Evel Knievel)