Tales of the Sea: HMAS Sydney vs. HSK Kormoran

The following facts are beyond dispute: A battle occured between HMAS Sydney and HSK Kormoran. Sydney and her crew were lost without a trace, while most of Kormoran’s crew escaped before the merchant cruiser sank.

Of the details, we have only the sometimes contradictory accounts of Kormoran’s crew. According to them, as Sydney drew within 1000 yards, the guns of Kormoran were uncovered and opened fire. Sydney was hit several times by Kormoran’s 6″ guns and once by a torpedo, and Kormoran’s anti-aircraft guns quickly cleared Sydney’s deck. The turrets of the light cruiser were heavily armored, and began to reply shortly. Although the firing positions on Sydney may have been knocked out early, at 1000 yards it would have been easy even for independently aimed turrets to find Kormoran. Kormoran received a hit in the engine room that rendered her immobile. Sydney, on fire and apparently out of control, drifted away.

Of the details, we have only the sometimes contradictory accounts of Kormoran’s crew. According to them, as Sydney drew within 1000 yards, the guns of Kormoran were uncovered and opened fire. Sydney was hit several times by Kormoran’s 6″ guns and once by a torpedo, and Kormoran’s anti-aircraft guns quickly cleared Sydney’s deck. The turrets of the light cruiser were heavily armored, and began to reply shortly. Although the firing positions on Sydney may have been knocked out early, at 1000 yards it would have been easy even for independently aimed turrets to find Kormoran. Kormoran received a hit in the engine room that rendered her immobile. Sydney, on fire and apparently out of control, drifted away.

As the ships drifted out of contact, it became clear to Commander Detmers (below, sitting, second from left) that Kormoran could not be saved. Her engine room was largely destroyed, and fires were threatening more vital areas of the ship. Kormoran would have to be abandoned. About twenty of Kormoran’s crew of almost 400 had died in the fight, and another couple dozen died during the evacuation when a lifeboat capsized. Most of the remaining men, however, were rescued by an Australian ship.

The survivors of Kormoran told their interrogators that they had last seen Sydney drifting to the north. After  she left visual range, an explosion was heard and a sheet of flame was seen on the horizon. As no survivors were found, it was assumed that a magazine explosion must have sent Sydney to the bottom. The 6″ hits, the torpedo, or fires started by the anti-aircraft guns all may have contributed to a fire that reached the magazines. Australian damage control was probably based on British practice, which did not have an inspiring record. For example, it is now thought that HMS Hood was lost not to a hit from Bismarck, but suffered an explosion as the result of a fire started by shell hits from Prinz Eugen, a heavy cruiser. Criminally negligent shell storage probably cause the loss of the ship. Especially in the case of Sydney, a ship which did not expect to find an enemy and which may not regarded Straat Malakka as much of a threat, it’s plausible to think that shell storage might have been lax. Moreover, ships that suffer magazine explosions often incur extremely high casualty rates; only six survived HMS Invincible, three HMS Hood, and two HMS Queen Mary.

she left visual range, an explosion was heard and a sheet of flame was seen on the horizon. As no survivors were found, it was assumed that a magazine explosion must have sent Sydney to the bottom. The 6″ hits, the torpedo, or fires started by the anti-aircraft guns all may have contributed to a fire that reached the magazines. Australian damage control was probably based on British practice, which did not have an inspiring record. For example, it is now thought that HMS Hood was lost not to a hit from Bismarck, but suffered an explosion as the result of a fire started by shell hits from Prinz Eugen, a heavy cruiser. Criminally negligent shell storage probably cause the loss of the ship. Especially in the case of Sydney, a ship which did not expect to find an enemy and which may not regarded Straat Malakka as much of a threat, it’s plausible to think that shell storage might have been lax. Moreover, ships that suffer magazine explosions often incur extremely high casualty rates; only six survived HMS Invincible, three HMS Hood, and two HMS Queen Mary.

On the other hand…. Hood, Invincible, and Queen Mary sank within minutes of suffering German fire. Men below decks had no opportunity to reach the deck, and there was no chance for liferafts and other survival equipment to be launched. Given what seems to be a long period of time between Sydney’s disengagement and her destruction, it’s puzzling that more men weren’t able to make it off the ship. The explosion may have been unexpected, especially if it was caused by poor shell storage, but there still should have been men on deck fighting fires. Even if the captain was dead, damage control teams should have been able to operate on their own. Sydney must have lost power (presumably because of flooding from the torpedo), as she would have moved off and engaged Kormoran at range if she could have.

Interrogation of the crew of HSK Kormoran shed no light on these question. Kormoran’s commander and crew remained in an Australian prisoner of war camp until 1947. Three weeks after Sydney’s disappearance, the Imperial Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor and embroiled Australia in the Pacific War. Much of the rest of the Royal Australian Navy was destroyed at the Battle of Java Sea and by Japanese aircraft carriers. The question of Sydney’s fate was, temporarily, put on the back burner.

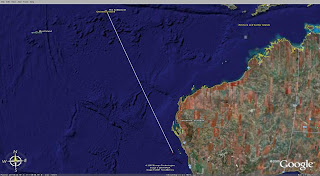

On Febrary 6, 1942, a life raft bearing a  dead man washed up on the beach of Christmas Island, over 2000km from the likely site of the battle. Although the remains could not be positively identified as coming from Sydney, it was believed at the time that the condition of the remains and the area of their discovery indicated that they were probably from the missing light cruiser. Unfortunately, no extensive inquiry could be made, as the Imperial Japanese Navy was in the midst of its six month rampage and invaded Christmas Island in March. The body was buried without marker in a military cemetary on the island.

dead man washed up on the beach of Christmas Island, over 2000km from the likely site of the battle. Although the remains could not be positively identified as coming from Sydney, it was believed at the time that the condition of the remains and the area of their discovery indicated that they were probably from the missing light cruiser. Unfortunately, no extensive inquiry could be made, as the Imperial Japanese Navy was in the midst of its six month rampage and invaded Christmas Island in March. The body was buried without marker in a military cemetary on the island.

In October 2006, a group seeking to identify the dead sailor found the grave and recovered the body. In the skull of the unidentified sailor, they found a 9mm bullet.

To be continued…