Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 1,617

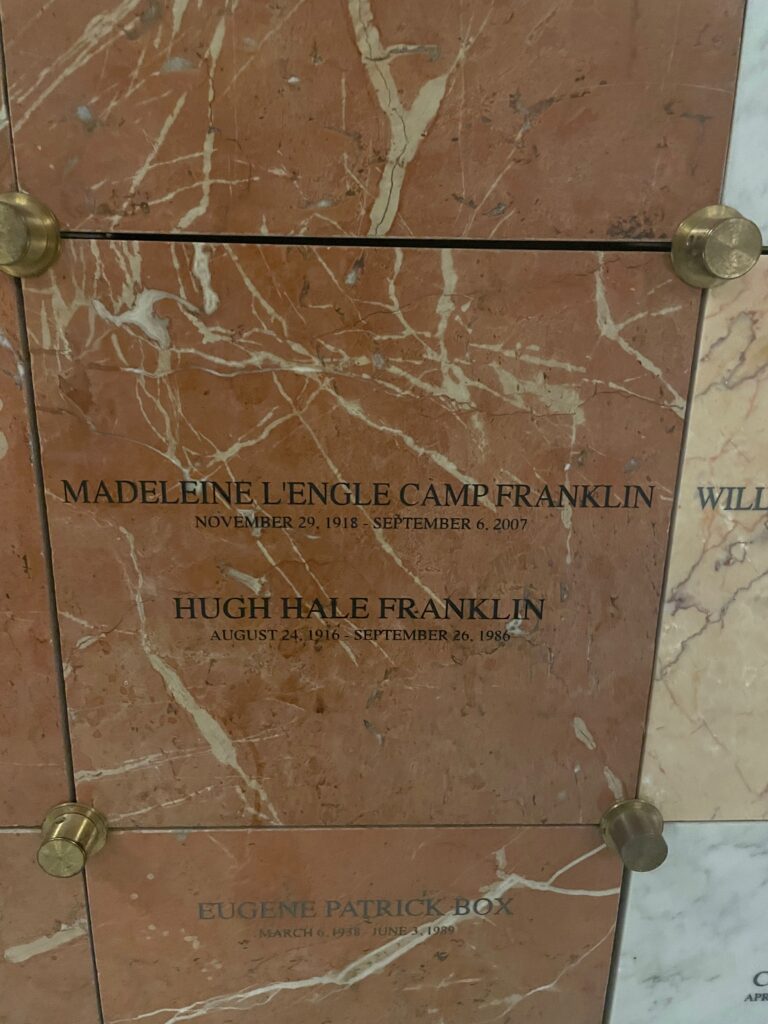

This is the grave of Madeline L’Engle.

Born in 1918 in New York City, Madeline L’Engle Camp grew up fairly well off. Her grandfather had founded a bank, her mother was a reasonably well-known pianist, and her father was a journalist and war correspondent, though he got gassed in World War I and never fully recovered from that. The family spent a lot of time in the French Alps, both because they had the money to do so and because they were looking for better air to help her father’s lungs. She attended boarding school in Switzerland and then a couple in the South in the 1930s as the family moved to Jacksonville. Throughout this period, she wrote stories, really from the time she was a small kid. She was extremely lonely in her childhood, both at home and at the boarding schools. Desperately looking for a world that accepted her, she began to create her own through her writings.

Camp attended Smith and graduated in 1941. She moved to New York, started publishing her first works, and soon married an actor named Hugh Franklin, also buried here. He was mostly a fairly minor theater guy until 1970, when he landed a role on a new soap opera called All My Children. He played a doctor on that show until 1983, when his hearing got bad and he couldn’t take cues anymore.

In 1945, Madeline L’Engle, as would be her pen name, published her first novel. The Small Rain was a bildungsroman novel about a lonely girl and pianist coming of age at a boarding school. But there wasn’t much market for this or her other early novels. None of them really sold well. The family bought a house in Connecticut, where she wrote and raised the kids and also was the choir director in a local Congregational church. She tried to publish and when she couldn’t and tried to give it up, but how could she? It was central to her sheer existence. It was so frustrating. On her 40th birthday, in 1958, she received yet another rejection notice. She saw it is a sign to give up. She tried again, but she just couldn’t do it. She had these words in her and they needed an outlet, even if no one bought them.

In 1959, L’Engle started a new novel. This was A Wrinkle in Time. This sci-fi novel for young adults is about three kids who go through space and time to rescue the father of one of them. Like most of her work, it was vaguely based on her own family. It was rejected. Again and again and again. In fact, it was rejected over thirty times. But somehow she was able to get the manuscript into the hands of John Farrar, the editor and namesake at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. He loved it and decided to publish it. I hardly have to tell you that it was a huge hit when it was published in 1962. She won the Newberry in 1963 for this.

After this, L’Engle could do almost anything she wanted. She continued publishing her own works, usually about a book a year, though there were some gaps in there. She also wrote for the New York Times about children’s books in a long essay in 1963. Most of her books were part of two series–the one around the kids from A Wrinkle in Time and then the Chronos series, which started with a 1960 novel called Meet the Austins that didn’t do well at the time but of course blew up after the Newberry win. Interestingly, in this initial book, the kids are not engaged in fantasy activity, but rather is another novel about a lonely orphan and the family who cares for her. But later in the series, sci-fi and fantasy themes do develop. Well, whatever works I guess. There were some stand-alone books too.

One major theme in L’Engle’s books is her strong Christian faith. But this was not your modern fire and brimstone evangelicalism. L’Engle was Episcopalian and her writings reflected her positive sense of Christianity, a version where universal salvation was possible. Due to this, many fundamentalist Christian bookstores refused to sell her books. We can’t have the kids thinking that most people are good after all. She also rejected the entire concept of divine punishment, so let’s just say that she and Jimmy Swaggart probably did not have a lot of conversations.

Today, L;’Engle is seen as one of the fundamental authors of children’s literature. A Wrinkle in Time remains beloved with multiple adaptations, including one directed by Ava Duvernay. Because of this, she receives serious literary criticism too. I thought this Paris Review essay quite interesting. It combines the memory of the author being so excited to meet her as a child and how disappointing that meeting actually was with a discussion of the “creepy authoritarianism” of L’Engle, though it seems to me that it was just that L’Engle sometimes wrote her characters as badly behaved and getting spanked for it.

L’Engle also rejected a lot of dismissive and condescending classifications she got for the type of book she wrote. As she once stated, “I’m not a children’s writer. I’m not a Christian writer. I resist and reject that kind of classification. I’m a writer period. People underestimate children. They think you have to write differently. You don’t. You just have to tell a story.” This all makes sense to me.

When I was a kid, I sort of missed out on most children’s fiction, so this is all kind of a big gap to me. I remember teachers trying to get me to read it, but I was more interested in learning about countries and real people and such at the time. I have no idea why and fiction is a huge part of my life now and has been ever since college. Guess I was a weird kid, which will surprise no one. Point is that I have no memory of reading L’Engle so I can’t offer anything personal here. I am sure comments can go into certain details and themes in much more detail than I do in this post.

L’Engle’s late life was dominated by bad health, especially osteoporosis. She died in a nursing home in 2007, at the age of 88.

Madeline L’Engle is buried in Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, Manhattan, New York.

Again, L’Engle won the Newberry in 1963 for A Wrinkle in Time. If you would like this series to visit other Newberry Award winners from this era, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Maia Wojciechowska, who won in 1965 for Shadow of a Bull, is in Santa Fe, New Mexico and Elizabeth George Speare, who won in 1962 for The Bronze Bow, is in Easton, Connecticut. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.