The economics of the early NFL

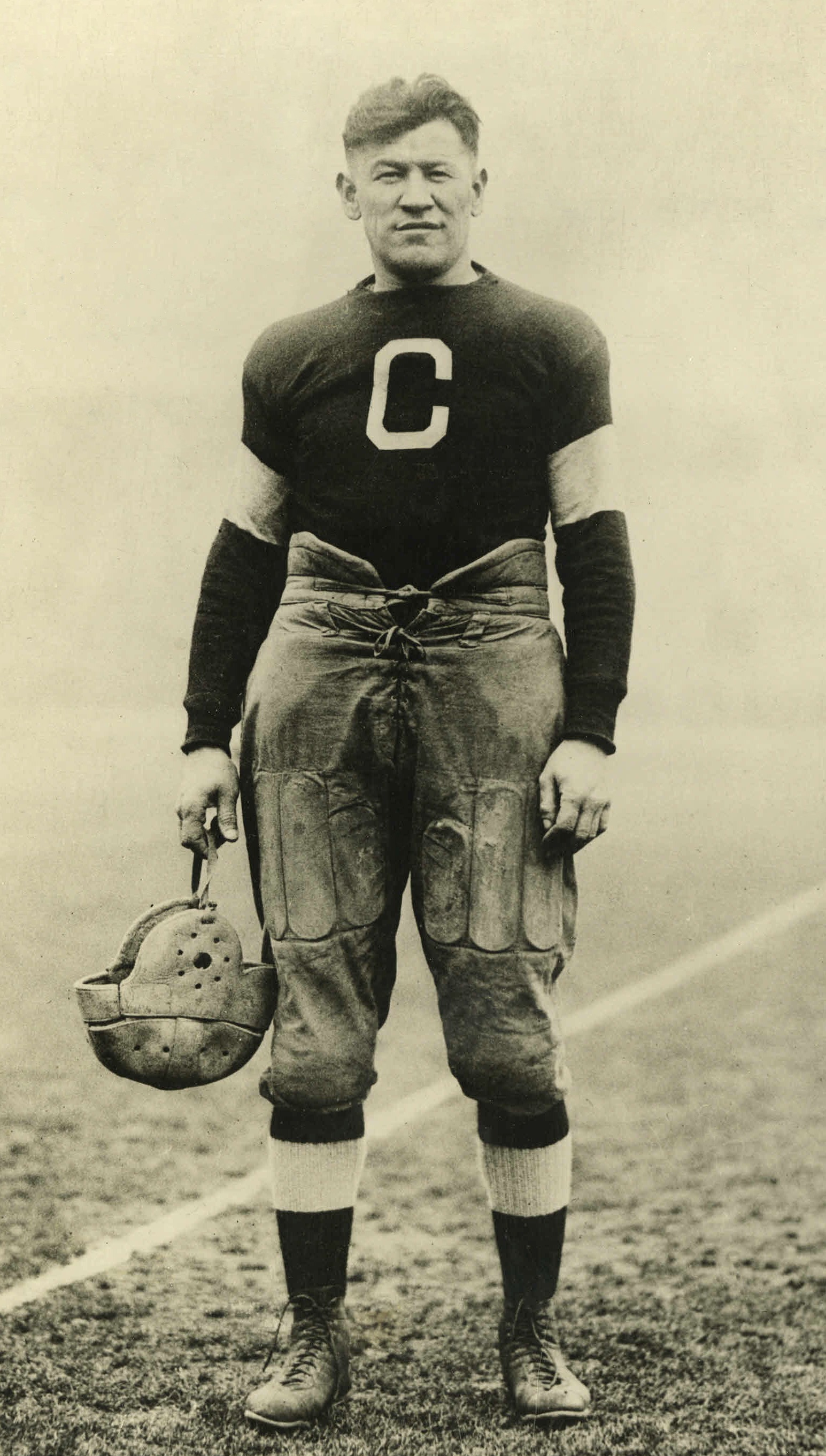

I’ve been reading a history of the NFL to my son (he’s doing a school project on Jim Thorpe, who was actually the NFL’s first president, although this appears to have been an essentially nominal appointment for publicity purposes), and I’ve become interested in the following question: Why did it take professional football so long to establish itself as a major part of the economic and cultural landscape in regard to sports in 20th century America?

The background story is this: For the first half of the century, college football was a much bigger deal in America than the NFL. Indeed the NFL didn’t even exist prior to 1920, in part because of some bizarre trope that football was a game for amateur gentlemen. The NCAA stridently opposed the very idea of professional football for obviously self-interested reasons, and indeed the Big Ten Conference (then called the Western Conference) went so far as to threaten to strip graduates who subsequently played in the NFL of their varsity letters retroactively. Note that these were players who had exhausted their college eligibility, so this wasn’t even an attempt to keep the NFL from raiding college rosters, which in any event the NFL barred itself from doing by league rule.

So for various reasons the NFL got off to a very slow start as a going concern, with many teams located in small towns all over the Midwest coming into the league and then folding after a few seasons. The initial economics of the whole thing were captured by the fact that the initial franchise fee to join was set at $100, at the meeting at the car dealership in Canton, Ohio, where the league was officially formed. According to George Halas, who was there as the part owner of the franchise that shortly afterwards became the Chicago Bears, there probably wasn’t even $100 in the room at the time.

The league eventually started to find some sort of economic footing, but very slowly. A key milestone was the signing of massive college football star Red Grange by the Bears in 1927, but even so throughout the 1920s and 1930s the NFL was a very small potatoes operation in comparison to sports such as major league baseball, college football, boxing, and horse racing.

How slow that growth was is highlighted by the following: In 1942, the at the time well-known actor Don Ameche wanted to buy a franchise and put it in Los Angeles. By then the NFL franchise fee was up to $50,000. Now on the one hand this illustrates that the raggedy 1920s operation had become a genuine going concern ($50,000 in 1942 was the equivalent of close to one million dollars today). On the other hand, it also meant you could buy your very own NFL franchise for the price of about nine median-priced houses, or, to put it sports terms, for less than Hank Greenberg had been paid to play baseball for the Detroit Tigers the year before.

Translating this into modern terms, the franchise fee for the next new NFL franchise in, say, London, England, will probably be around four billion dollars, which is about 10,000 median-priced houses, or 100 Justin Verlander annual salaries.

Anyway, I find it interesting that professional football took so long, relatively speaking, to become a big money enterprise, especially given the great popularity of college football, which challenged major league baseball for the title of America’s most popular team sport throughout the first half of the century. I find it particularly interesting that the whole absurd ethos of amateurism clung to the sport so much more powerfully than it did to baseball. (College baseball for some reason never became a big deal). Jim Thorpe — the biggest college football star of his age — was stripped of his Olympic track and field gold medals because he had picked up a few dollars playing minor league baseball during the summer while in college. This was a common practice at the time, but Thorpe didn’t bother to play under an assumed name for the purpose, and got caught, which caused a huge scandal.

Again, the idea that football players should be amateurs was weirdly embedded in the cultural narrative for a long time. I suspect this may have something to do with Teddy Roosevelt’s obsessions with the masculine virtues of the sport in the context of an Ivy League education (I mean I’m basically going to blame Harvard for something if there’s any opportunity to do so), but it was definitely a thing, and it may well have played a role in keeping the NFL a small time operation for longer than it otherwise would have been. And the remnants of that ideology seem to have helped college football become a multi-billion dollar per year annual business before any players were finally paid over the table for their talents. (Such payments are still limited to name, image, and licensing contracts).