Genteel Union-Busting in the Ivies

Like many of you, I was overjoyed to hear that the NLRB had ruled that graduate students in private universities once again have the right to form a union. This case was especially meaningful to me, because I was an undergraduate when Columbia University graduate students last tried to organize and ran headlong into the 2004 Brown decision.

As a result of this experience, I’m entirely unsurprised that Columbia’s response to the ruling is to threaten an appeal and put up a union-busting website. Thanks to the training that I acquired at Columbia, I can tell you that Columbia is a historically union-busting institution: President Seth Low personally approved the use of Columbia students to help bust a national machinist worker’s strike in 1901, and the tradition continued with Columbia students acting as strike-breakers in a 1905 transit strike, a 1920 railroad strike, and a building trades strike in 1936, until the rise of student leftism finally made collegiate scabbing uncouth.

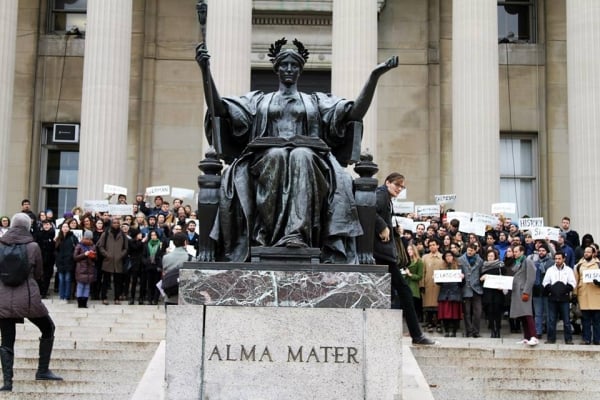

And again, I was there when the GSEU held a “Free the Ballot Box” protest on the steps of Low Library to protest management having locked up the ballot boxes in the NLRB election that had been held shortly before the Brown decision, which election had come only after four years of management stalling and failed appeals that dragged on for years after the NLRB had made its ruling in 2000 granting the right to organize.

Well, as an alumni, an eight-year veteran as a unionized graduate student and union activist, and currently unionized adjunct, I thought I’d check out the website, and see what union-busting looks like up in Morningside Heights.

Well, Provost Coatesworth’s letter is a bit more politely worded than most union-busting websites, but the arguments haven’t changed a bit:

“Dear fellow members of the Columbia community:

Yesterday, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) reversed a position it has held for the past 12 years and decided that students at private universities may be treated as employees for the purposes of the National Labor Relations Act when they are appointed to positions as teaching assistants or research assistants. The decision overturns a 2004 ruling involving Brown University.

Columbia and many of our peer universities have challenged this position.”

It doesn’t exactly burnish the laurels of an institution supposedly devoted to higher learning to start its argument in a way that would get them docked if they handed in this letter in their required Logic & Rhetoric course. As the graduate students who normally teach this course might point out, they’re rather leaving out the fact that the position the NLRB just reverse was itself a reversal of a ruling made four years prior, which rather undercuts the suggestion that the NLRB is somehow unfairly breaking with stare decisis.

And when the Provost begins to talk about the actual workers involved, the level of argument gets even worse:

Nearly all of the students at Columbia affected by this decision are graduate students. We believe that the daily activities and the advisor-advisee relationships involved in the scholarly training of graduate students define an experience that is different from that of the typical workplace. Being a graduate student can take many years of intense research, teaching and study. But unlike university employees, graduate students who serve as teaching or research assistants come to this institution first and foremost to acquire through that work the knowledge and expertise that are essential to their becoming future scholars and teachers.

The first implicit argument here is a very old canard that graduate students aren’t actually workers. This argument was disproven to my satisfaction back in 2004 when my French TA brought in his W2 form and pointed to his name where the form said “employee” and Columbia University where it said “employer.” Graduate students perform research and teach classes, just like the other researchers and teachers that Columbia hires to research and teach; the fact that they also take classes doesn’t change this fact.

We then get into the real anti-union discourse when the Provost starts talking about the upcoming election:

Students whom the NLRB determines are eligible to vote will soon have an opportunity to express their own views on this matter in an upcoming election, on a date to be announced by the NLRB. All those eligible to vote in the election will weigh for themselves the potential benefits and drawbacks of having their interests represented by the United Auto Workers. For my part—and, in this, I speak for my colleagues in the University administration and for many faculty members—I am concerned about the impact of having a non-academic third-party involved in the highly individualized and varied contexts in which faculty teach and train students in their departments, classrooms, and laboratories.

Over the past decade, Columbia’s schools have made great strides in addressing a number of stipend and quality-of-life concerns. We have established a productive dialogue with the Graduate School Advisory Council and with other student organizations that has resulted in enhancements for PhD as well as MA students. The University will continue on this path not only because it is right, but also because it helps us attract the very best students in the world.

There is a certain sublime un-self-awareness in a third party to a union election – since Provost Coatesworth is not a graduate student who gets to vote on whether or not to form a union – warning against the dangers of third parties involving themselves in the relationship between faculty and graduate students. But stripped of the high-minded concerns and interest in dialogue and right, these are boilerplate union-busting arguments:

- Pointing to past wage increases and company unions as proof that a union isn’t necessary.

- Trying to other the union as a “non-academic third-party” as opposed to an organization made up of academic workers.

- Injecting the views of senior and middle management in order to raise the specter of retaliation from above.

Since Provost Coatesworth hasn’t ever taught at an institution where graduate students are unionized and doesn’t have much practical experience in this field, allow me to speak from a position of expertise. Graduate student unions don’t get involved in academic advising or the classes that graduate students take for their coursework, or their dissertations, so we don’t interfere with “faculty teach[ing] and train[ing] students in their departments, classrooms, and laboratories.” Where we get involved is in the interactions between managers and workers, whether those workers are teaching assistants, graders, tutors, research assistants, or adjuncts. We get involved when workers are being told to work more hours than they are being paid to work, we get involved when workers are being told they have to walk their manager’s dog or do their drycleaning, we get involved when managers sexually harass their students. Because the thing that Provost Coatesworth doesn’t want to admit is that those “highly individualized and varied contexts” are ones in which management have total power over their subordinations, not just in their current employment but their future career as well, and unions give workers a voice in their working conditions.

As someone who grades essays for a living, I have to say that I wouldn’t give this a a passing grade. The argumentation is sloppy, it ignores a wealth of experience in the field, and worst of all, it’s plagiarized.