A People’s History of the Marvel Universe, Week 6: This Man, Magneto!

Face front, true believers!

When it comes to the intersection of politics and Marvel comics, the X-Men’s “mutant metaphor” is justifiably at the forefront. Up until now, I’ve danced around the topic a little because I lost a detailed set of notes that I had made on the original Lee and Kirby X-Men and Claremont’s entire run and am still in the process of reconstituting my research.

This means that my discussion of the “mutant metaphor” will have to build gradually, which is actually rather appropriate because I intend to argue in several succeeding columns that the “mutant metaphor” was something that took a good bit of time to emerge in the X-universe and as a theme ultimately owes far more to Chris Claremont’s work than to Lee and Kirby.

One example of this is the character of Magneto, the X-Men’s original antagonist who is often held up as the Malcom X to Professor Xavier’s Martin Luther King. There’s a lot of problems with this analogy, as I’ll discuss in future issues, but to the extent that there’s any truth to it, it’s entirely the result of Claremont’s run, because the original Magneto from the Lee and Kirby years is unrecognizable from his appearance in X-Men #114 through #161, and is frankly not that great a villain.

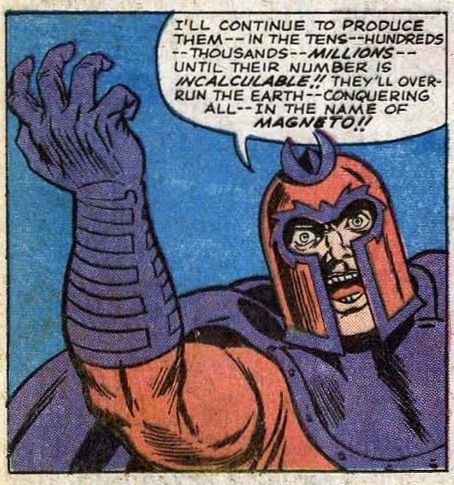

To begin with, Magneto’s motivations in the Silver Age are so generic and opaque that he decides to name his mutant revolutionary group the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. This kind of stuff is the weakest part of the Silver Age, because the adage that “everyone is necessarily the hero of his own life story” speaks to a truth of human nature. Almost everyone, even sociopaths and sadists, feels the need to construct ideological frameworks and narratives which justify and legitimize their actions. But the closest that Silver Age Magneto gets an ideology is a crude Social Darwinism which posits an inevitable race war between humans and mutants in which mutants must rise up and subjugate humanity (which becomes more problematic when you consider the Silver Age depiction of anti-mutant prejudice…more on this in a future issue):

Despite these shortcomings when it comes to motivation, Silver Age Magneto could have been a more impressive antagonist if he was presented as a figure with some dignity (like Doctor Doom) or wit (like Loki). Unfortunately, Lee and Kirby depict the master of magnetism, the would-be messiah of mutantdom, as a straight-up Snidely Whiplash villain. To begin with, Magneto is repeatedly and habitually abusive to his underlings, especially to the cartoonishly obsequious Toad, who he makes wear a metal belt specifically so that Magneto can torture him with his mutant powers.

In addition, he’s also a lousy manager. He shows a blatant disinterest in his subordinates’ safety, makes it blatantly clear that he will throw each and every one of them under the bus the moment it can gain him the slightest of advantages, and repeatedly abandons them in moments of peril to save his own skin:

It’s not that these qualities can’t be part of a villainous background, but it doesn’t particularly fit a villain who aspires to be the leader of an entire race of people. At the end of the day, there’s just not enough Toads in the world who would be willing to follow someone who calls them cannon fodder to their face. The only way that Lee and Kirby explain why anyone would ever follow this guy, especially why they would continue to follow him after the first time that they get foiled by the X-Men, is that he’s a consummate gaslighter and emotional manipulator. Hence his long history of constantly holding over the heads of Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch the one time he “helped” them, as well as pretending to be the father of both (plus Polaris):

Again, this isn’t adding to the portrait of a villain who impresses anyone. Add onto that the way that Magneto compounds this callousness with a sadistic streak that runs to the quasi-genocidal (which I think is where, if we’re in the mood to be charitable, Jeph Loeb got his idea from for Ultimatum), and you’ve got a real heel:

But of all of Silver Age Magneto’s personal behaviors, I find none so foul as the occasion where, to put it bluntly, he decides to pimp out the Scarlet Witch to Namor to gain his support.

There’s not really another way to interpret this scene, especially with the way that Kirby depicts Magneto pawing and leering at a shrinking Scarlet Witch in the manner of a cliffhanger serial villain tying a damsel in distress to the train tracks. All of this is truly despicable on a personal basis, but the reason why I argue that, in all the ways that really matter, Chris Claremont created Magneto as we have come to know him, is that Lee and Kirby’s Magneto is a Nazi (and I don’t make that claim lightly):

As I’ve mentioned before with reference to Captain America, Jack Kirby especially was not a man to make such comparisons lightly or accidentally, given his anti-fascist sympathies and service in the European Theater in WWII. Each visual detail – from the goose-stepping soldiers wearing M armbands and knee-high patent leather boots to the WWII era Stalhellms and forage caps and submachine guns – is meant to evoke not just fascism generally but Hitler specifically. And this is simply not compatible with the identity that Chris Claremont would develop of Erik Lensherr, the Holocaust survivor who bases his belief that humans will inevitably attempt to exterminate mutants on the fact that he saw genocide against supposedly dangerous genetic minorities first-hand. (Arguably there’s an interesting story to be told of a survivor so traumatized by their experiences that they seek to become the figure of their own nightmares, but that’s not a story that Lee and Kirby were telling.)

However, there are a few redeeming virtues of Silver Age Magneto that explains why he was revived when other antagonists like Unus the Untouchable were left in the circular file of history. The costume’s red with purple accents and the distinctive helmet are an iconic Jack Kirby design that would be carried forwards for decades (although in recent years he’s been rocking an all-white variation of same). And while Stan Lee didn’t have that good a fix on Magneto’s political ideology, he did have something that almost made up for it – a complete lack of understanding of how magnetism actually works. This allowed for some truly wacky moments while giving Magneto a useful power set for a powerful villain:

While the Magneto-turning-guns-against-their-wielders trick is a good one (that predates X-Men: First Class and Days of Future Past by several decades), this is basically magnetism-as-telekinesis, which Magneto will use to block Cyclops’ eye-beams or fly through the air. And it only gets goofier from there:

While I’m willing to grant Lee and Kirby that there might be enough dust with a high content of iron or nickle or the like to spell out a giant skywriting message (and the cursive signature is an uncharacteristically dashing touch), Magneto’s hypnosis-by-magnets is clearly a callback to the long-discredited ideas of Franz Mesmer, who believed that you could use magnets and one’s own “animal magnetism” to cure diseases and mental illnesses.

However, a snazzy costume and a lack of understanding of magnets work is a thin reed to build a major antagonist on, which may be one reason why Lee and Kirby kept marooning Magneto on alien planets or de-aging him into baby. To make Magneto something more than a Snidely Whiplash, Chris Claremont would have to do some rewrites…which we’ll discuss the next time A People’s History of the Marvel Universe covers the X-Men!